Malcolm Is Abusive, Not Marie

Your support is paramount to our plan to scale our efforts, which include a new children’s book series, three new novels, more life giving merch, and providing free therapy for those in crisis. We can’t do that without your support. Our newest book, I’m NOT Okay, Thanks for Asking is available here. We have tons of merch for purchase here. If those don’t float your boat, please consider making a contribution here. Thank you.

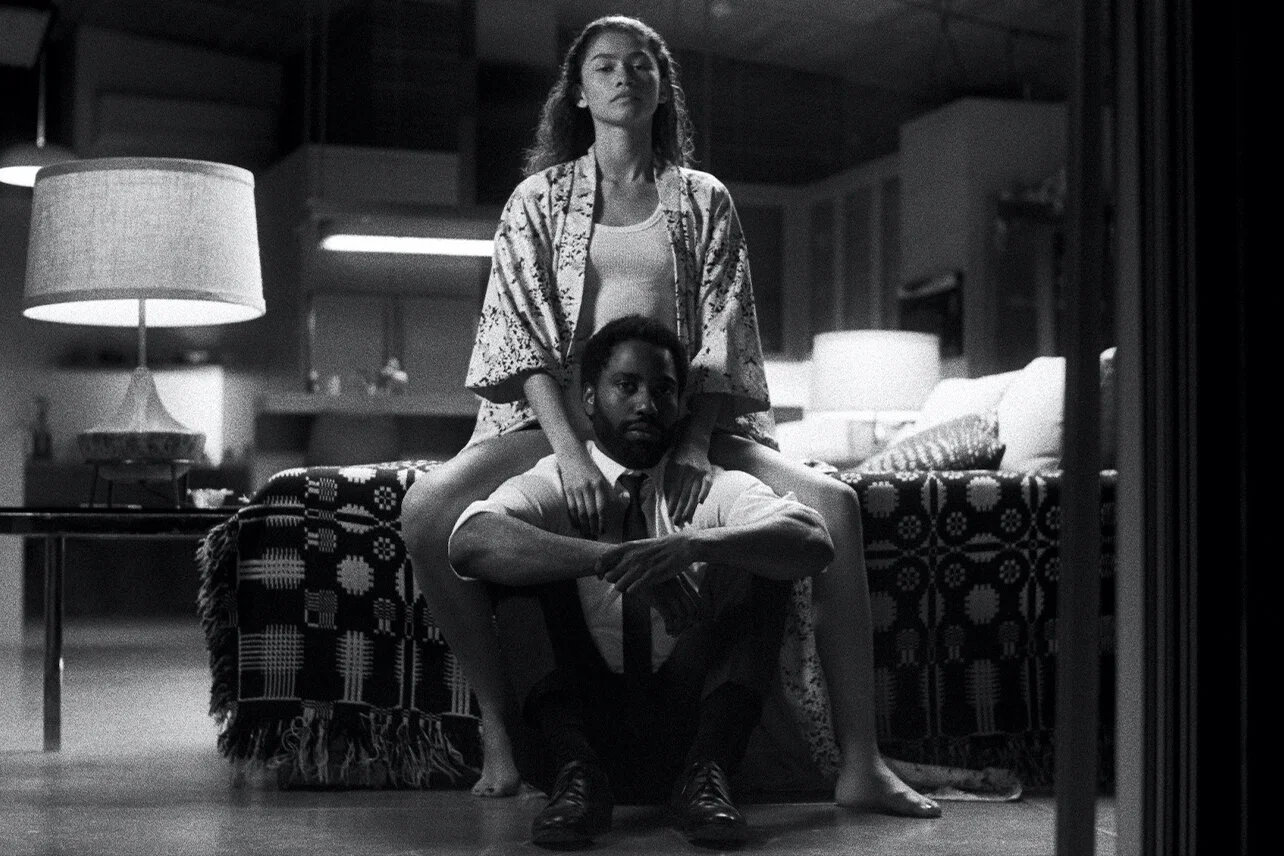

You’d be excused for saying you haven’t taken the time to watch Malcom and Marie. The basics are that it stars Zendaya (Marie) and John David Washington (Malcolm). That the two are a couple. That they argue… a lot. That Malcolm is a filmmaker and Marie is his partner that has overcome more trials in life than anyone should have to encounter. That Malcolm is verbally and emotionally abusive.

That’s it.

What’s most concerning about the film is the aggregate of reactions I’ve glimpsed on social media. If all you knew about the dynamic between the two was from tweets or FB posts, you’d be inclined to assume there’s equal culpability in a clearly not-meant-to-be relationship. And while Marie certainly comes with noticeable baggage, the film prides itself on being an exploration of a relationship, not a stroll down I-owe-you memory lane. No, it’s not about placing blame. No one has to be more wrong or right than the other, but when the scales of disproportionate are so blatantly clear, it’s both rational and justified to call them out.

Marie’s grievances are valid, but most importantly, they’re present. They stem from the most impactful professional happenings of Malcolm’s life at the time.

But what about Marie? What about her belittling of Malcolm? Her attempts at emasculation? And anything else you hang your linchpin of patriarchy on?

The seminal moment in the film isn’t any of these never ending fights the two are involved in. It’s near the beginning, when a physically and emotionally drained Marie cooks Malcom a meal, tells him she’d rather talk in the morning, and affirms her adoration for him with an “I Love You.” If you don’t think that should count for something, perhaps a reexamination of understanding your partner should be front and center.

Marie, seemingly more emotionally intelligent and self-aware, knows next to nothing positive will come from taking the conversation any further at that moment, yet Malcolm persists. Boundaries are important, even in relationships. So too is respect for your partner as an equal human being. Malcolm persists under the selfish guise of not being able to go to bed knowing Marie is mad at him, and so, the bell rings for round 2 of the fight. In real life, how many years pass before that whole “never go to bed mad at each other” fairy tale dissipates to the reality of human emotions?

While the pre-awards season train worked overtime to build momentum around a Best Actress nod for Zendaya, it’s Washington that deserves some also-ran Academy Award attention. The ability to make any character as insufferable as Malcolm was from beginning to end takes a Herculean effort.

Maybe this is the rare film that would’ve been much better as a play. Maybe both artists lacked the range to tell such a story within the confines of drawn out, sublime writing. All of those things may or may not be true, but in the end, Malcom and Marie just turned out to be an excruciatingly hard film to watch. You didn’t scrape through it because you actually cared what happened. As a twenty minute short film, this would’ve been an absolute masterpiece. As a feature length, it just doesn’t work. At all.

A Complete Unknown gives us elite performances, though it leaves you wanting more.

The Coen brothers’ 2009 exploration of a modern-day Job calamity is vibrant and comedic with just the right amount of despair.

Richard Linklater’s latest film isn’t necessarily a coming of age story, but an animated time machine to 1960’s White America. At least it’s done well.

Describing their relationship as toxic is a misnomer. Their interactions, much like the film, are decidedly obnoxious.

Judas and the Black Messiah is the film that it is, not the film we want it to be. That’s the point.

Some things always seem better left unsaid and unchecked, and that’s a really big problem.

Might the 2020’s shake out to be the largest exploration of Black-centered cinema, ever?

The Little Things Add Up, Just Not How You Might Expect

Even in 1952, Black people fell in love too! And some lived happily ever after.

The Last Black Man in San Francisco’s central theme isn’t so much gentrification, but Black male friendship – and the struggle to find and retain it