The Harlem Renaissance of Film?

Your support is paramount to our plans to scale our efforts, which include a new children’s book series, three new novels, more life giving merch, and providing free therapy for those in crisis. We can’t do that without your support. Our newest book, I’m NOT Okay, Thanks for Asking is available here. We have tons of merch for purchase here. If those don’t float your boat, please consider making a contribution here. Thank you.

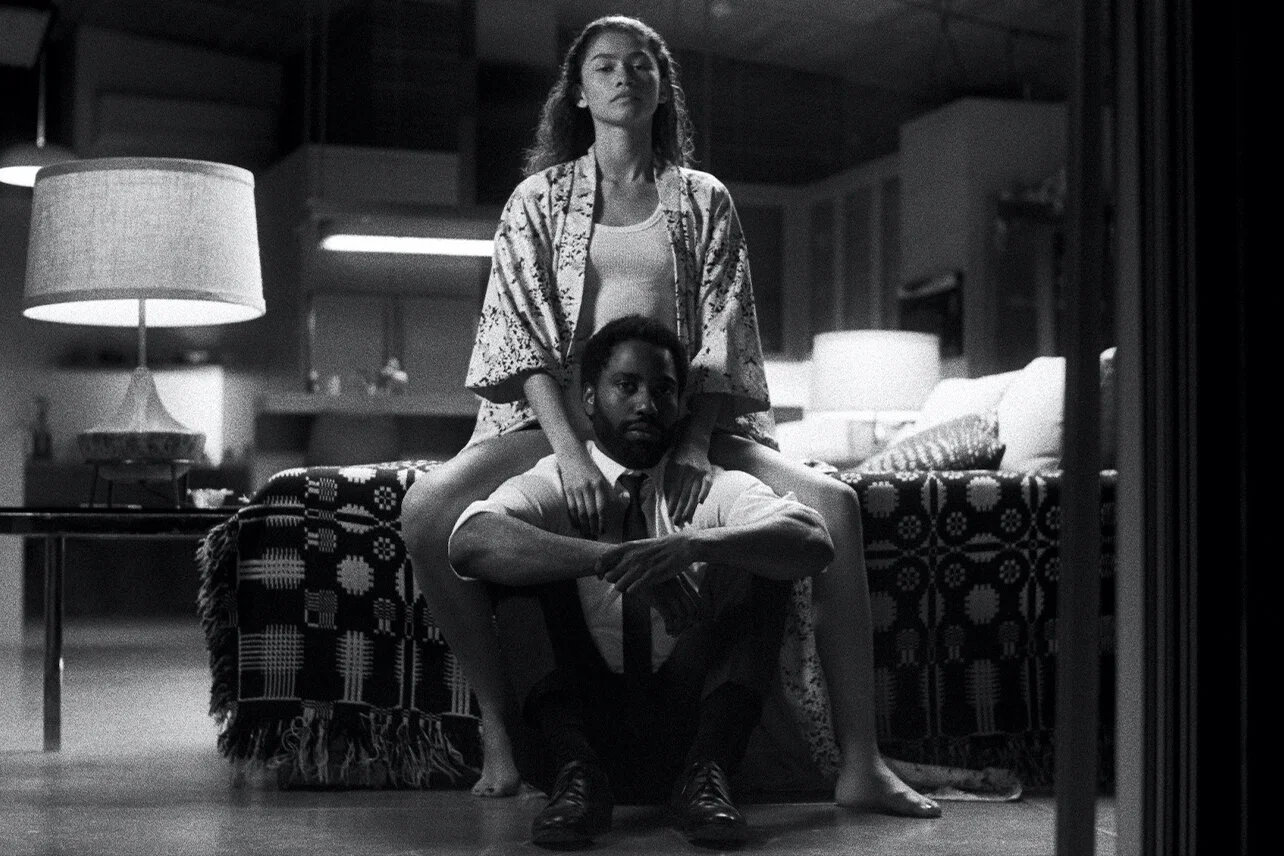

Judas and the Black Messiah is now open in theaters and available on HBO Max

While most of this decade has failed to meet our early expectations (hey there, global pandemic!) there are some promising respites across the artistic landscape. For starters, many of 2020’s best podcasts focused on, told the stories of, or were written and directed by both rising and prominent Black talent. Tyler R. Tynes brought the backstory of former NFL MVP Cam Newton to light with The Cam Chronicles. Floodlines dives into the true story of Hurricane Katrina’s impact on New Orleans, with illustrative emphasis on a nuanced tragedy that has become that violent family incident America hopes to erase by simply not talking about it. Tessa Thompson’s The Left Right Game is the best piece of art you’ve never heard of.

Yet as we creep into awards season, the onslaught of film being released that focus on sharing the Black American experience is a wonderful anecdote to an otherwise depressing time. Hollywood, for whatever reason, seems to have recently caught an itch for Black-centered cinema.

When it comes to mainstream recognition, perhaps the most notable year for Black talent was 2002, when at the 74th Academy Awards, Denzel Washington, Halle Berry and Sidney Portier each took home the night’s most admirable honors. Yet much has been made about the roles it took for both Washington and Berry to finally get their just do, and the following decade did little to quell the notion that Hollywood was interested in Black cinema, but only a certain kind of film. The times seem to be a changing.

One can argue that film is a subcontractor designed to uphold and project the values of any thriving democracy. It’s not enough to just put out films about certain characters, you need to put out the right films. Birth of Nation helped perpetuate fears of racism so effectively that we’re still grappling with them today. The FBI used Hollywood as a means for bolstering the public’s perception of the organization in its early years. Anti-communism propaganda became an industry of its own during the Cold War. This decade, at least in its infant stages, provides a glimpse of hope that Hollywood will remain committed to telling the holistic nature of the Black experience, not just ones about slavery or Jim Crow.

Sylvie’s Love is a timeless romantic drama about love, and our innate desire to find it. It’s so well-written, produced and dramatized that I found myself ashamed at the end of it. I braced myself for some scene rooted in anti-Blackness. For the first time in my life, I confronted a startling truth – even in 1952, Black people fell in love. And it sometimes ended in happily ever after.

Malcolm & Marie isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, but it’s a mainstream film that permits an unambiguous Black couple to show that their relationship has extreme peaks and valleys, like almost everyone else.

Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom gives us all the undeserving pleasure of taking in the late Chadwick Boseman’s final on-screen performance with the delight of Viola Davis, with plenty of jazz, soul, dance and introspection sprinkled in.

The United States vs. Billie Holiday shines light on one of music’s most beloved icons and tells the story of a brilliant and beautiful artist that has been glorified in her death while being ostracized in life, which is too often the story of Black artists.

Judas and the Black Messiah is a long overdue tale of the state sanctioned assassination of Fred Hampton, and how his work to unite all oppressed people across racial, ethnic and gender lines via the Rainbow Coalition was the line that could not be crossed for the power structures of 1960’s White America.

There’s also All In: The Fight for Democracy, MLK/FBI, One Night in Miami, and so much more. And if you’re hoping to get lost in majestic performances, look no further than Nicole Beharie in Miss Juneteenth, Radha Blank in The Forty-Year Old Version, and Delroy Lindo in Da 5 Bloods.

One of the defining features of prejudice in the American way-of-life is the fear of “other”. Namely, if we do not know someone of a certain background or feel as if we can’t identify with their existence, we justify our subtle dismissiveness of their humanity. Yet as a student of history, I’ve learned that it doesn’t take being dropped in 1981 to feel like you were there. Technology has allowed us to learn one another in ways never before imaginable.

The most comforting thing about the depth of Black centered film this year isn’t so much that Black people are in it, but rather that so many stories are being told about us. We’re not just former slaves, drivers, maids, or drug dealers. There’s complexity, nuance, joy, triumph and loss in our everyday lives, as is the case for all people groups around the world. When you present opportunities for others to see themselves in you, over time, it makes it harder to be committed to misunderstanding their plight. I mean, that’s the hope anyways.

Beyond watching any of the above works, here’s a resource with even more ways you can support and uplift Black filmmakers.